I have put The Firehouse Jazz Band Fake Book up here. It’s a very useful resource, and the internet archive – from where I got it – doesn’t seem to be responding right now.

Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ Category

A resource for vintage jazz players

October 20, 2025Revisiting Artificial Intelligence.

November 7, 2024[This piece has been inspired by reading about the University of Maryland’s new cross-disciplinary Artificial Intelligence Interdisciplinary Institute at Maryland.]

I’ve written and spoken quite a lot about AI, about how AI has changed its meaning since the term was introduced in 1956, or about technical issues, or about neuromorphic implementations, or even about the possible dangers of AI. But now, I want to write about the new directions that neurobiologically inspired AI is taking.

AI (as it currently stands, as of November 2024) is the result of the convergence of several technologies.

- the internet itself (allowing free and easy interconnectivity)

- lots of people and organisations using the internet, and posting vast amounts of data (text, sounds, graphics, images etc.) on it, making them freely available

- many years of research into adaptive systems such as neural networks

- and, of course, the electronic technologies that underly cheap digital computing and communications, the enabling technology for all of the above.

This technical convergence is having huge social effects well outside of technology.

The industrial revolution changed what was valued in people: being strong was no longer important when machines could provide power. Are we coming to a point where intelligence will no longer be important when machines can provide it? And if so, what will matter? What do we actually want from AI? And who wants it, who will control it, and to what end?

It is, of course, not quite that simple. Strength is quite easy to define, but intelligence is much more difficult. Chess-playing machines don’t replace chess players (even if they could) because the interest is in the game itself: the existence of a perfect chess playing machine would not stop people playing chess. And the nature of intelligence in chess playing machines is not applicable directly to other problems. We currently have machines that learn statistical patterns and regularities from enormous volumes of data, and we use these in conjunction with generative systesm which produce text without any understanding of it. These systems are trained, and this training uses many thousands of computers over a long period of time. This is so expensive that very few companies can undertake it. Accessing or using these trained machines is much less expensive, but relies on the trained system being made available.

Fortunately (or unfortunately) progress in AI is rapid. I am not referring to the use of AI, but to the underlying ideas. And these new ideas will revolutionise the way AI can be used. There is another convergence of technologies at work here: the convergence of neurophysiology and microelectronics. For many years researchers have worked to understand how neurons (brain cells) work and communicate, and this research is starting to produce results that could underlie a much better understanding of what underlies real intelligence – and hence allow better approximations of artificial intelligence. Current systems use a very basic concept of the neuron (in neural networks), but new ideas – specifically two point neurons, modelled on pyramidal neocortical neurons – are arriving. These are much more powerful for many deep mathematical/ statistical reasons, and one result of this much more powerful algorithm is that less computing power should be necessary to make them work. This could enable democratisation of training AI systems.

Perhaps more importantly, some researchers suggest that the way in which these neurons co-operate (rather than compete) may be critical in making the whole system work. Bill Phillips’ book “The co-operative neuron” analyses how this may work in real brains, but it is only a matter of time before the concepts are implemented electronically. This has huge implications because for the first time we begin to understand the way in which the brain produces the mind. And our electronic technology may be able to recreate this. Such synthetic intelligence could be very different from the relatively unsophisticated systems that we currently call intelligent.

This makes the development of interdisciplinary institutes like the one recently set up at the University of Maryland timely and critical. We urgently need the humanities here. These developments are too important to be left to the technologists.

Interfacing electronics and neural cultures: brain organoid (artificial?) intelligence:

October 15, 2024There have been major advances in culturing neurons (and associated brain cells), and integrating them within electronic circuits. There’s an excellent review on Frontiers in Science. There are two possible aims for this work: understanding neural circuitry better (with many clinical applications), and integrating neural circuitry into artificial intelligence systems (because real brains are much better at certain types of everyday tasks).

Back in the ealy 2000’s I worked (with Nhamo Mtetwa) in this area on an EPSRC project including Glasgow University (Prof Adam Curtis, Prof Chris Wilkinson, Brad Dworak) and Edinburgh University (Prof Alan Murray, Dr Mike Hunter, Dr Nikki Macleod). At that time Stirling was involved in data analysis, intended for data from multi-electrode array (MEA) based cultures of early rat neurons, . But culturing them proved almost impossible for us, and at Stirling we worked on data from the Potter/Wagenaar lab at Georgia Tech. I gave a talk about the area in Georgia Tech in April 2003. But a great deal has changed since then: we were too early (or perhaps just not inventive enough!) to the game.

Possibly the biggest change is in the source of the neural culture. The use of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) from human skin samples, and the building of 3-D brain organoids (small cultures of neural and associated cells) means that one need not be sacrificing newborn rats, and secondly that the cultures are (at least in a sense) made from human-like neural cells. This, and improvements in the size and flexibility of electrodes (and faster processing of their signals) means that such cultures can much more reliably be built and instrumented. But how should this work be continued? There is a long discussion in the Frontiers paper, itself part of a larger discussion on Frontiers, including a very good discussion of ethics issues. Should we be seeking better understanding of the brain, improving our ability to deal with clinical issues (mental health and physical damage to neural tissue), and/or incorporating these organoids into AI systems?

It is clear that better understanding of brains (and more generally nerve tissue) has clinical applications. It may raise philosophical issues as well: once we understand the connection between consciousness, awareness, cognition and neural tissue, we may need to re-jig our ideas of what makes an addictive personality, or of makes people criminal, quite apart from the possibility of re-creating these in synthesised neural cultures. But that is (probably) a little further down the road.

Incorporating organoids into AI systems has attractions. While real brains run at much lower speeds, they are highly parallel and very energy efficient, more than compensating for this. However, neural tissue needs to be kept at a constant temperature and perfused with nutrients and water. While microfluidics have advanced a great deal, I reckon that these disadvantages may make putting such systems into consumer equipment unattractive. In addition, such systems have a limited lifespan compared to the (essentially infinite) lifespan of semiconductor based electronics. Further, there are still issues related to the longevity of the electronics/tissue connection. On the other hand, in the 1980’s I never expected to see hand-held devices with 64 bit processors and many gigabytes of memory, so one can never be sure!

Lastly, I want to return to the attempts we made more than 20 years ago. It seems to me that I have been trying to make scientific/technological advancements too early. Without iPSCs, without good microfluidics, creating and keeping neural cultures alive was very difficult, making instrumenting them just too difficult (at least for us). And before that, I was working on a binaural hearing aid that attempted to find the sound sources, and allow the user to select the one of interest using an iPad-like interface – but in the year 2000. Too early. Right now many researchers are refining Transformer-like AI systems, jumping on a fast-rolling bandwagon. Too late. Getting the timing just right is the really difficult trick!

Deepfakes and the Law

January 29, 2024Deepfakes are a serious problem. It’s now relatively easy to create speech, images or videos that give the strong impression of being real recordings of people, even though they are made up. By using images of peoples faces (particularly from videos) and recordings of the speaking it is possible to create very lifelike “recordings” of them speaking or acting. This is oiften seen as downside of Artificial Intelligence, but it has little to do with intelligence, and much more to do with engineering a basis of functions that can be combined to produce realistic data. [Is this intelligence? Maybe…]

I asked Bard what ir thought about the law and deepfakes

Can creators or publishers of damaging deepfakes be prosecuted under defamation laws?

and here’s the answer it gave:

Whether creators or publishers of damaging deepfakes can be prosecuted under defamation laws is a complex legal question with no easy answer. It depends on a variety of factors, including the specific jurisdiction, the content of the deepfake, and the intent of the creator or publisher.

Arguments for prosecution under defamation laws:

- Deepfakes can be just as damaging as traditional defamation: They can harm someone’s reputation, lead to lost job opportunities, and even cause emotional distress.

- Deepfakes are often used with malicious intent: They can be created to spread misinformation, damage someone’s reputation, or even extort money.

- Defamation laws are designed to protect people’s reputations: They should apply to deepfakes just as they do to traditional forms of defamation.

Gavel and sound block (image)

Arguments against prosecution under defamation laws:

- Deepfakes are often difficult to distinguish from real videos: This can make it hard to prove that a deepfake is actually defamatory.

- Defamation laws are intended to protect against false statements: If a deepfake is based on real events, it may not be considered defamatory even if it is damaging.

- Prosecution of deepfakes could infringe on freedom of speech: There is a concern that laws against deepfakes could be used to censor legitimate criticism or satire.

The current state of the law:

- There is no specific law against deepfakes in most jurisdictions. However, some countries are considering or have already passed laws that could be used to prosecute the creators or publishers of damaging deepfakes.

- In the United States, for example, some states have laws against cyberbullying and revenge porn, which could be used to prosecute the creators of deepfakes that are used to harass or humiliate someone.

- In the European Union, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) gives people the right to control their personal data, which could be used to argue that deepfakes that use someone’s image without their consent are illegal.

Conclusion:

The legal landscape surrounding deepfakes is still evolving. It is likely that we will see more laws and court cases in the coming years that will help to clarify whether or not the creators and publishers of damaging deepfakes can be prosecuted under defamation laws.

I hope this information is helpful. Please let me know if you have any other questions.

There’s been a fair amount of discussion on this from the legal establishment:

https://www.farrer.co.uk/news-and-insights/ahead-of-the-algorithms-deepfakes-and-the-law/

https://www.nelsonslaw.co.uk/artificial-intelligence-deepfakes/

https://www.ashfords.co.uk/insights/articles/deep-fake-meets-real-law

https://lawdit.co.uk/readingroom/can-defamation-be-used-to-protect-victims-of-deepfakes-part-2

https://www.farrer.co.uk/news-and-insights/the-legal-issues-surrounding-deepfakes-and-ai-content/

(Thanks to LF for these)

What really hits me from all this is that the law takes a long time to catch up with new developments. The issue of anonymous posting makes prosecution very difficult. The ease with which the companies which share posts can get away with washing their hands of any responsibility is, to me, indefensible.

I don’t know the way forward: but eventually the law needs to catch up.

Artificial Intelligence and its Dangers.

December 27, 2023An apology

I’ve been really remiss: I haven’t updated this blog for more than two years. But perhaps today (Storm Gerrit outside, with wind and heavy rain) is a good day to get back to it.

Artificial Intelligence

I recently gave a talk on Artificial Intelligence (AI) to a group of retired academics (Stirling University Retired Staff Association, SURSA). As an academic, I worked on related matters for many years, and remain involved in AI. This was a non-technical talk, to academics from many disciplines. It went down well, and led to lots of discussion.

It also led to me talking to quite a variety of people about AI after the talk, as I felt more able to take a broader perspective on AI than I had as a researcher, where I necessarily concentrated on some tightly defined areas. This led me to thinking more about both the possible dangers of AI research in the near future.

What are the dangers of AI?

A great deal has been written about the existential dangers of AI: I’m less than convinced. Firstly, because AI, at least as matters stand, is only intelligent in certain senses. It lacks volition (or will) entirely, which to me means that it’s not about to take over or enslave the human population of the Earth. (I note that intelligence with volition, as is to be found in humans, has indeed taken over and enslaved parts of the animal and plant kingdoms).

Secondly, current AI systems are generally deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs) mixed with systems for generating text, and sometimes logical inference engines. These are made up of a number of components which, while not new, can take advantage of major advances in computing technology, as well as the vast amount of digitised data available on the internet. Often they are used as a user-friendly gateway on to the WWW, enabling quite complex questions to be asked and answered, instead of searching the internet using a set of keywords. This is an intelligent user interface, but not intelligent in human terms.

Of course, such systems can replace humans in many tasks which currently are undertaken by well-educated people (including the chattering classes who write newspaper articles and web blogs!). Tasks like summarising data, researching past legal cases, or writing summaries of research in specific areas might become automatable. This continues a process started with the spinning jenny, and running through the industrial revolution where human strength and some artisanal skills ceased to be a qualification for work. While this is certainly a problem, it is not an existential one. The major issue here is who has the power: who (and how many) will benefit from these changes, which makes this a political issue.

I am more concerned about volition.

As matters stand this is not an area that is well understood. Can intelligence, volition and awareness be separated? Can volition be inserted into the types of AI system that we can currently build?

I don’t think this is possible with our current level of understanding, but there is a great deal of research ongoing into neuroscience and neurophysiology, and it is certainly not beyond imagination that this will lead to a much more scientificically grounded theory of mind. And volition could well be understood sufficiently to be implemented in AI systems.

Another possibility is that we will discover that volition and awareness are restricted to living systems: but are we trying to build synthetic living systems? Possibly, but this is an area that has huge ethical issues. Electronic systems (including computers) are definitely not alive in any sense, but the idea of interfacing electronics to cultured neural systems is one that has been around for quite some time (though the technical difficulties are considerable).

In conclusion: should we be worried – or how worried should we be?

There are many things that we can be worried about, ranging from nuclear war, to everyday land wars, to ecological catastrophies, to pandemics. Where might AI and its dangers fit within these dangers? From an employment point of view, AI has the capacity to remove certain types of job, but equally to create novel forms of job, dealing with data in a different way. I am not a great believer in the capability of governments large or small being able to influence technology. Generally, governments are well behind in technological sophistication, and have rings run round them by technology companies.

We do need to think hard about giving systems volition. Yet equally we do want to build autonomous systems for particular applications (think of undersea or space exploration), which would provide some reasons for research into awareness of the systems environment. This could require research into providing certain types of autonomous drive, particularly where the delay between anyone who might control the system and the system itself is large. But rolling out such systems with volition, without careful safeguards could indeed be dangerous. But what form might these safeguards take, given that governments are generally behind the times, and that these systems are produced by large independent technology companies primarily motivated by profit? This is a difficult question, and one to which I do not have an answer.

Jamming on Jamulus

October 24, 2021

A very pleasant little Jam just now, on the BeatRoute server (in Frankfurt), with someone from Aachen and someone else from Macedonia. Lovely. My setup really works well (it’ll probably break now that I’ve said that!), though sometimes it needs turned on and off once or twice before it comes up. And I seem (i) to have to turn on the interface and e-piano after booting, and (ii) to have to set up the connections in Jack every time, can’t see any way of saving them.

But that said, and once it’s up, it works really well, letting me play through Reaper into Jamulus without noticeable additional latency.

They say that it’s an ill wind that blows nobody good: one good thing to come out of all the Covid-based lockdown is playing with other folk from the comfort (?) of my garage studio!

Jamulus and Ubuntu Linux

October 11, 2021For quite some time I’ve been using Jamulus, to allow me to play music with other musicians over the internet: it’s a really good (and free) distributed system, where musicians play in real time with other musicians (1). Each musician uses a Jamulus client, and this communicates with a Jamulus server. There’s lots of servers in lots of different places, divided up into a number of genres (I use the Jazz genre most of the time). The critical thing is that the delay between the musicians client and the server is low – best to be less than 60 ms, preferably a lot less. And it really needs to use a wired connection to your local (household) router, to avoid delays caused by the wireless connection. I often play with musicians in different countries in western Europe, using servers located in London, Berlin or other parts of western Europe.

I set up a server in my own house, wired to my router, and set up to be visible from outside, so others can use it too. This uses a headless Raspberry Pi 4: a nice little machine that sits beside my router, and just seems to keep running and running.

The reason for this post, however, is my solution to a hardware problem. My original client system was an ancient and very heavy Mac Pro (early 2008), and an even older MOTU 828 (about 2003 or so) firewire interface, both old and out-of-date equipment from my University, long since replaced with more recent kit. This worked spectacularly well for a long time: however, I then had problems with the firewire interface failing sometimes. Being stingy, I initially decided to purchase another equally ancient MOTU 828 (for all of £50!): this worked for about a week, until the same problems happened again. I concluded that the issue was with the Mac Pro, and I wasn’t about to try to mend this. It didn’t really owe me anything.

In the meantime, I’d been interested in using a Raspberry Pie as a desktop. But when I tested it, it was just too sluggish for me. But I knew that one might be able to get a faster ARM-based 64 bit computer, particularly since Apple were now selling them. However, being tight-fisted, I wasn’t keen on buying a new Apple machine.

A little investigation led me to the Odroid N2+ machine. It has “a quad-core ARM Cortex-A73 CPU cluster and a dual core Cortex-A53 cluster with a new generation Mali-G52 GPU”, and is much, much cheaper than a Mac! (of course, you have to supply a monitor, keyboard, mouse etc., but still…). It runs Ubuntu 20.4, which is perhaps not as nice as MacOS 11, but as someone who used Unix on a 25 by 80 terminal for years I wasn’t too worried about this. In fact, the Ubuntu user interface is really quite nice.

A little work on the net showed that you need to install Ubuntu studio, with the low latency kernel, Jack to connect different audio software together, and Jamulus itself. I also installed Reaper, my favourite DAW. These were all straightforward, installed using apt. Jamulus itself had to be built (for the ARM 64 architecture), but there were instructions in the downloadable tarball. (You could also try the installation scripts at https://github.com/jamulussoftware/installscripts, but I didn’t notice them till just now!).

So how well does it work? Obviously, I had to replace my MOTU 828 as well, and I had a Rubix 44 which I now use. I believe that most USB audio interfaces will work (but note that Jamulus always uses 48K samples/second). Once I had sorted out some problems (I had loopback enabled, accidentally on the interface…), and learned how to use Jack (easy, once you know how!), off it went. And I could use Reaper at the same time with minimal increase in latency, allowing me to add echo or reverb, or to use a VST piano sound from a MIDI input. That was something that the old Mac Pro couldn’t quite manage.

Altogether? I’m really impressed with the Odroid N2+. I’m learning more about how to use Ubuntu (I can remember how to use vi, and lots of Unix terminal commands, but for everyday use, one can work very well using the mouse-based user interface that comes with Ubuntu). I get a lot less dropout in the sound than I did: I’d always assumed this was coming from the network, but now I realise some of it was from the Mac Pro not being up to the job.

I’ve bought another Odroid N2+, just to play with it (I don’t want to risk stopping the first one from being available for playing and recording music). I’ve connected the old disks from the Mac Pro (all 3 Terabytes) using a USB 3 cradle, and I can read and write to them (in their native Mac format). I’m thinking that having a number of small machines round the house for specific tasks is the way forward, now that one can get powerful systems for about £100!

(1) For the technically minded, the crucial thing is that it uses the UDP protocol: for technical details, see this paper by Volker Fischer.

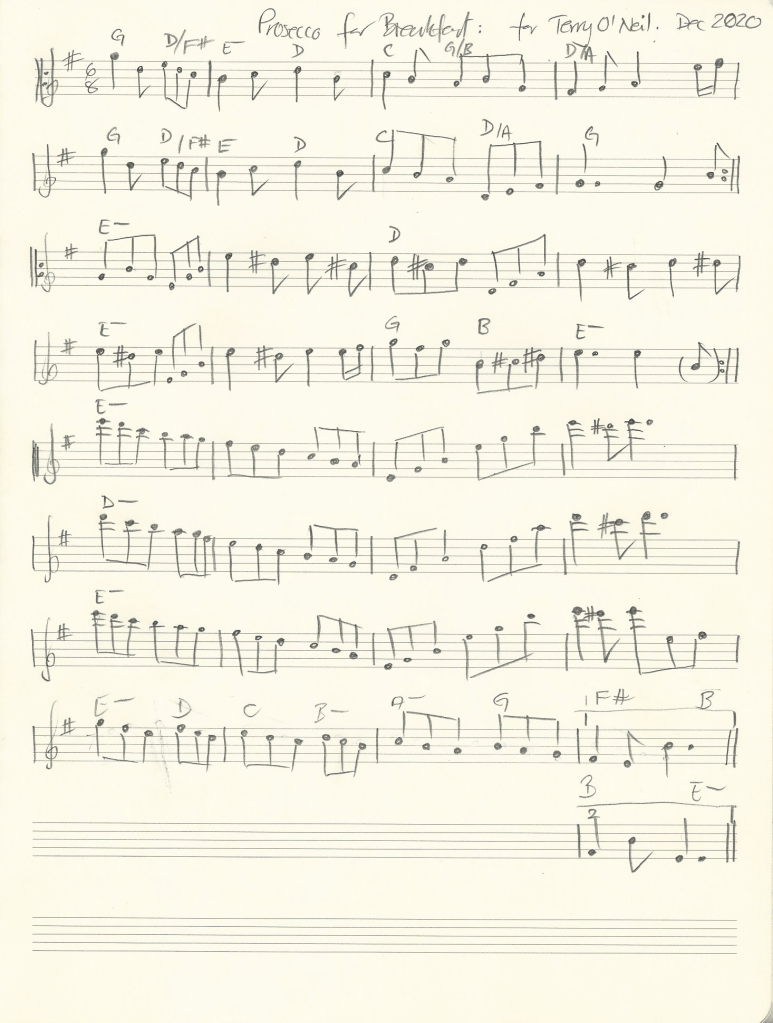

“Prosecco for breakfast”

December 23, 2020At Dunblane Folk Club, we have gone virtual, and hold a Facebook Watch Party on Sunday nights. After the last one, one of our stalwarts, Terry O’Neil said that at Christmas she would be having prosecco for breakfast. Now, there’s a well known tune called “Whisky for Breakfast”, so I reckoned that “Prosecco for Breakfast” would be a good title for a tune. Perhaps a jig…

And here it is.

and here’s a piano version…aaargh.. I can’t upload sounds to this page. I have put it on SoundCloud: here’s the link to it.

Hassibi et al’s (Deepmind) protein folding predictor

December 1, 2020I’ve been using the protein folding problem as an example of a really hard problem in computing for a long time: that and real-time weather forecasting have been used by many as part of the case for supercomputers making a real difference.

This new work is an improvement on their 2018 technique (see https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1923-7.epdf), and is based on deep learning and gradient descent. Now their 2020 technique is an improvement on this (see https://deepmind.com/research/open-source/computational-predictions-of-protein-structures-associated-with-COVID-19 and https://deepmind.com/blog/article/alphafold-a-solution-to-a-50-year-old-grand-challenge-in-biology).

Whys does this matter? Proteins are absolutely central to life on Earth: they are the building blocks of all living entities. Proteins are complex (very complex) molecules made from strings on amino acids, but their behaviour is tightly loud up with their spatial conformation. So if one knows the string of amino acids, one might be able to predict their behaviour. However, their behaviour (what they will react with, how they will change their conformation in electric fields etc.) is very hard to predict from their chemical structure – it needs their conformation as well.

This new advance starts to make determining their structure directly look more possible. And this matters not just for understanding the behaviour of existing proteins, but for predicting the behaviour of synthesised proteins as well.